Empowering heritage artists through digital storytelling and awareness of intellectual property rights

by Diego Rinallo, Kedge Business School

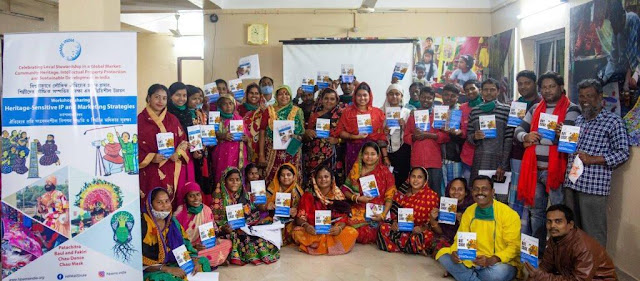

In the HIPAMS India project, we co-created heritage-sensitive intellectual property and marketing strategies with folk artists from three communities in West Bengal. These artists and their cultural heritage were in the past promoted by NGOs and government agencies, but were rarely the protagonists of their own activities. With the HIPAMS project, we attempted to empower artists with various capacity building initiatives aimed to familiarize them with social media and their use for digital storytelling, as well as raising awareness about their intellectual property rights as artists (our toolkit is available here). At the end of the project, we asked some artists to reflect on the outcomes of these capacity building initiatives.

Increasing awareness of IPRs was an important expected outcome of the project. For example, Baul artist Rasidul Islam is now aware of the commercial benefit of being named: “when a photograph or work of any artist is being promoted, if the name of contact is given the artist also gets promoted with the art form” but note that “in most of the cases the artists are used without any recognition”, which is “not at all a good practice”. As a result, he now has very clear expectations of what constitutes appropriate behavior: “When the videos of the art form are uploaded by anyone, courtesy must be given to the artist, the name, contact. A few words about him must be shared. So that people who are interested can connect to the artist. I don’t have any problem regarding sharing a photograph or a video of an artist, I just want that the name and contact must be provided”.

We were aware that the artists likely would not be able to enforce them, and this led to the decision to co-create ethical codes to inform audiences about how the artists would have wanted to be treated. Unexpectedly, greater awareness of one’s IPRs – independently from art codes – empowered artists in their relationships with clients, festival organizers, distributors, film makers, and other third parties. In the words of artist Biren Kalindi, this awareness helps not only evaluate past misbehaviors, but also direct action for the future: “I worked in 7 movies . . . where our art was recognised but our names were not given. The names of the cast and crew are given but our names are nowhere to be found. Now I have understood, so I will claim the recognition whenever a booking comes”.

Making artists the protagonists of their own promotion was the main goal behind the digital storytelling training. Many informants suggested that thanks to such training they indeed learnt about social media and marketing. As a result, they can design and implement their own marketing actions. Chau dancer Gourab Chowdhury says that “I have my own YouTube channel. Previously I was unable to upload my videos, but after the workshop I was trained to do so. I have created a group in Facebook which has around 2.5K members”. He continues: “I have learnt to make short films and use hashtags for better promotion. Using proper hashtags led to receiving of better publicity”.

Many artists also observed that they were able to reach, sell to, or perform in front of very distant audiences. For example, Baul artist Nityapriya Mandal wonders that they were able “to communicate with the global audience through webinars which would have been impossible without the social media trainings” and that thanks to such exposure, now “people are visiting our homes to listen to our music”, and she expects “that many more will come”.

Given their greater exposure, artists have improved their individual reputation. The term they more often use is ‘recognition’, which regards not only relationships with “the market” (current or potential clients, distributors, other commercial parties) but also their social standing in their communities. Thanks to their social media activities, some artists, such as Baul singer Rina Das Baulani now realize that “now many people know about me”. When reputation is limited, artists have to ‘push’ oneself in commercial transactions and convince potentially uninterested buyers of the value of their products or performances. In contrast, higher reputation means that the client will come and look for the artists, already knowing who they area and wanting what they have to offer, which puts them in stronger commercial position. Rina Das Baulani is flattered that “people call us to know where our Ashram is located” and that on one occasion “while returning from a program, a man came and asked me about my ashram. He also asked whether he can bring few guests with him

Exposure thus might lead to increased social status for artists. Sanjay belongs to the Chau dance community, whose artists in the past faced difficulties from their families when choosing to engage with this art form, which was not considered a valuable professional career Mousumi Choudhury, who is quite known as one of the first women Chau dancers, explicitly make a link between her reputation as a female artist in a traditionally male-only performing art and the possibility to attract more women in the future by saying: “I want women to come forward and take part for flourishing the traditional art form of Purulia”.

During our initial workshops with artists, we also asked them about the ‘roots and fruits’ of their tradition, which possibly contributed to a heightened sensitivity towards one’s innovation (the ‘roots and fruits’ tool is available here). Mousumi Choudhury was involved in a new Chau play which is “a bit different from original Chau performances”, named Mukhos khola, much dekha. Traditionally, Chau dancers are men only, so when performing fully clad with Chau masks, the audience might not be aware that dancers are female. So this play deviates from traditional Chau dance as at a given point, masks are opened to show the female dancers.

Artist Dharmendra Sutradhar made some Chau masks made based on traditional patterns, but adopting new, ecofriendly materials such as grains and cereals. Chau mask makers typically use flashy plastic items to decorate masks – the use of natural items is in this sense a ‘retro-innovation’ triggered by new environmental sensitivities, but that probably revitalizes heritage skills that have been forgotten. The artist had to re-invent how to use and colour natural times as nobody remembers how these items were used in the past.

Dharmendra Sutradhar has also made new products that are unrelated to the Chau mask making tradition. These include “an Egyptian pyramid out of paper pulp, metallic in colour” and “an African primeval man”. He’s however well-aware that this is something different from the tradition: “We have our traditional list of masks, but I want to create something new. Our forefathers have made products integral to our heritage and I have no intention of disrupting it. Old is gold: we cannot detach ourselves from it. But I’d like the upcoming generation to know, and say that I have created something unique”.

The Covid-19 pandemics has struck the traditional artists involved in the Hipams India project like everybody else in the world. Some, thanks to their new digital skills, were however better equipped to deal with these challenges. One notable example is patachitra artist Swarna Chitrakar, who composed a song and created a scroll to educate about sanitary measures to prevent contagion that made the domestic and international news.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rNbQ5N59ZXE&t=6s

In her song, Swarna expresses hope for a time in the not so distant future when “we will all be together and spend time in happiness”. We hope that this time is near, and that in the future, traditional artists will be able to prosper thanks to their art and pass it on to the new generations.

Comments

Post a Comment